LIKE FATHER

He’s out in the front yard on some kind of tractor, pushing a big snowplow blade to gouge out long strips of sod. I know he’s mad at me again for not being there to help him in the yard, but just as always, he won’t say anything. So there we stand, surveying the missing patches of lawn as the neighbors begin to peek through their window blinds. He must have some kind of plan, but he’s not going to let me in on it.

The sun is directly overhead and I can still feel the creases from the bed sheets on my cheek when I find myself rubbing it. I wonder if I should go and find a shovel somewhere.

You probably should, he says. And I should probably give you some money for helping, but what’s the use? You never end up with anything to show for it.

That’s okay, I say. If you weren’t so dead, maybe I’d ask you just what you think you’re doing with that plow.

I’ll never be that dead, he says, and climbs back on the tractor. And there we stay, surveying everything that’s been lost.

Mark Vinz

TOTEMS

Around here, just about every town has put up some kind of monument—animals, usually, from prairie chicken to walleyed pike, from turkey to otter to largemouth bass, sunning themselves through the long afternoons by the highway, waiting for some passer-through to stop and stare.

It started years ago when a traveling monument salesman passed through these parts, convincing mayor after mayor that their towns needed their very own identifying symbol in concrete or fiberglass. Just think how envious all those other towns will be, he’d tell them, when you unveil your masterpiece! People will start re-routing their trips just to visit your town!

He’s still out there, still traveling from town to town, only this time it’s traffic lights he’s selling. You can find them in the most surprising places, suddenly awakening to blink their eyes and glare at traffic, even when there isn’t any, when there’s nothing in sight for miles.

Mark Vinz

THE CIRCUS

for Jason Heroux

Dag T. Straumsvåg

—translated from the Norwegian by Robert Hedin and the author

SIRKUS

til Jason Heroux

Dag T. Straumsvåg

—translated from the Norwegian by Robert Hedin and the author

STARES

Dag T. Straumsvåg

—translated from the Norwegian by Robert Hedin and the author

BLIKK

Dag T. Straumsvåg

—translated from the Norwegian by Robert Hedin and the author

TRYING TO WRITE A DECENT POEM ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS

is like Benny turning to the kid beside him as they lean on the paddock fence, watching the jockeys appear with their mounts, asking Who do you like in the sixth?, the kid wearing argyles and loafers, madras shorts, a golf shirt. He’s got a racing form and a Dutch Masters cigar clutched in his fist and is squinting at the tote board, but he’s eleven years old and realizes he has been traumatized by a father who prowls the house in cinder-colored briefs. A thousand or so men loiter at the fence or on the benches nearby or inside the clubhouse, some with binoculars, some with coffee and éclairs. It doesn’t change the fact that they worship an anvil buzzing around in a haloed lather before dropping on their skulls. Benny could use a little tutelage, as could the kid, who starts to realize life can last a long time whether you’re lucky or not, and if you can’t exactly flee it maybe you can at least divert yourself from its nastier aspects, the way a bed skirt obscures the toenail clippings beneath. The paramedics lean against the meat wagon, smoking. Benny and the kid await the embolismic bugler with doubts in their hearts as thick as potato salad.

Daniel Pinkerton

SQUID SATURATION

The first giant squid washes up on shore and the beachcomber who discovers it scratches his head and says “Huh.” It’s early, the sea and sky shades of gray one might call “indecision.” The giant squid is also gray. Even the word “gray” appears unsettled. I worry I’ll be considered standoffish, continental, if I use the wrong spelling. The next person nudges the giant squid with a piece of driftwood. The squid shudders and soon expires. Other people happen by and take pictures. Some scientists come and haul the giant squid away. What if another even larger species of squid were found? What would that mean for the giant squid? Would the adjective become ironic? Would it be renamed the Fairly Big Squid? More giant squids start to wash up, lots of giant squids at regular intervals, still very much alive, flopping ashore on this otherwise nondescript beach where the scientists wait with giant saltwater tanks mounted on flatbed trucks to rescue and study the once rare living specimens. Squids or squid: they’ve never been seen in any numbers, so no one’s sure what to call a group of them. A school? A convoy? This makes them seem wishy-washy. Are they common or rare? Why not more vividly hued? Soon enough we grow to hate the giant squid, slimy and putrid with bulging eyes, centerpiece of every aquarium in the country, on billboards, in documentaries and magazine fold-outs. The giant squids are spoiling everything. They’re not mysterious or mystical, they just propel themselves through the water like a regular squid or octopus or some other member of that family, mollusk, cephalopod, whatever it is. They don’t taste very good. They don’t do tricks with beach balls or spray water out of a blowhole. When attendance drops, aquariums start releasing the giant squids. Even the president chimes in. “Personally, I don’t like being confronted by them.” It’s such an apt description, our encounters with the giant squid somehow aggressive, invasive, the way wealthy people feel when harangued by the homeless on their way to the symphony. This year everyone has started following the exploits of the rare snow leopard. The snow leopard is a creature about which we can read brief online articles or watch YouTube videos and not feel confronted, which we appreciate.

Daniel Pinkerton

DIET PEPSI’S ORIGIN STORY, 1964

Jeffrey Hecker

OHIO INVADES PENNSYLVANIA, 2031

Jeffrey Hecker

Mark Vinz is Professor Emeritus of English at Minnesota State University Moorhead. From 1971-81 he was also the president of Plains Distribution Service and editor of the poetry journal Dacotah Territory, and Dacotah Territory Press from 1973-2007.

His poems, prose poems, stories, and essays have appeared in over 200 magazines and anthologies; his most recent books are Permanent Record (poems), The Trouble with Daydreams: Selected and New Poems, and a memoir, Man of the House: Scenes from a 50s Childhood. He has also co-edited several literary collections, such as Inheriting the Land: Contemporary Voices from the Midwest and The Party Train: A Collection of North American Prose Poetry.

He is also the recipient of the Kay Sexton Award “in recognition of long-standing dedication and outstanding work in fostering books, reading, and literary activity in Minnesota.”

Dan Pinkerton lives in Urbandale, Iowa.

Dag T. Straumsvåg has been employed as a farmhand, sawmill worker, librarian, and sound engineer for a radio station in Trondheim, Norway, where he has lived since 1984. He is the author and translator of eight books of poetry, including A Bumpy Ride to the Slaughterhouse (2006), The Lure-Maker from Posio (2011), both from Red Dragonfly Press, and Nelson (Proper Tales Press, 2017).

Robert Hedin is the author, translator, and editor of two-dozen books of poetry and prose, most recently At the Great Door of Morning: Selected Poems and Translations, published by Copper Canyon Press, and as editor, The Uncommon Speech of Paradise: Poems on the Art of Poetry, White Pine Press. He lives in Frontenac, Minnesota.

Jeffrey Hecker is author of Rumble Seat (San Francisco Bay Press, 2011) & chapbooks Hornbook (Horse Less Press, 2012), Instructions for the Orgy (Sunnyoutside Press, 2013) & Ark Aft (The Magnificent Field, 2020). Recent work appears in South Dakota Review, Yalobusha Review, and Posit. A fourth-generation Hawaiian-American, he teaches at The Muse Writers Center & reads for Quarterly West.

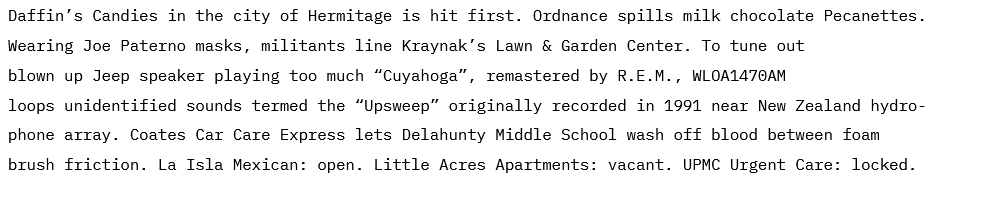

Cover Image credit: “Sea-Esel” (Sea Monk).

Der Naturen bloeme, Mscr 70,

Lippische Landesbibliothek Theologische

Bibliothek und Mediothek.